Ladakh is famous for its culture, beautiful landscape, crystal clear Pangong-tso, Nubra’s sand-dunes, Changthang’s pashmina, lush green valleys of Kargil, the beauty of Zangskar, the forts that dot the landscape and so on. Ladakh still holds many secrets and unexplored mysteries. I recently explored one such mystery.

There is a village called Sharchay in Kargil district of UT Ladakh. The village is located at an altitude of 10,000 ft (3,050m) above mean sea level (msl). The village is surrounded by towering mountains that seem to hide more than they reveal. The village dates back to ancient times. It came to the forefront in the 20th Century as it is located on the approach route used by mountaineers to climb Mount Gyunkar, whose peaks stands at 18,000 ft (5,487m) above msl. An elder in the village mentioned that till middle of the 20th Century there were no restrictions in these areas and people were able to travel around freely. He explained that many mountaineers used to visit this area before the Partition of 1947 and the creation of the Line of Control between India and Pakistan that cuts through this landscape. At the time, climbers would trek down from Mount Gyunkar towards Sharchay and then follow the route along the Indus to Mount K2 in Baltistan.

The village still lacks road and phone connectivity and continues to struggle for these amenities. The village is famous for its agriculture and fruit production especially walnuts and apricots. It is also famous for the high quality of pure Salajeet, which is used in traditional medicinal systems, found around the village. The inhabitants of the village are considered to be one of the oldest Dardic communities in Ladakh, who are believed to have migrated from Gilgit many centuries back.

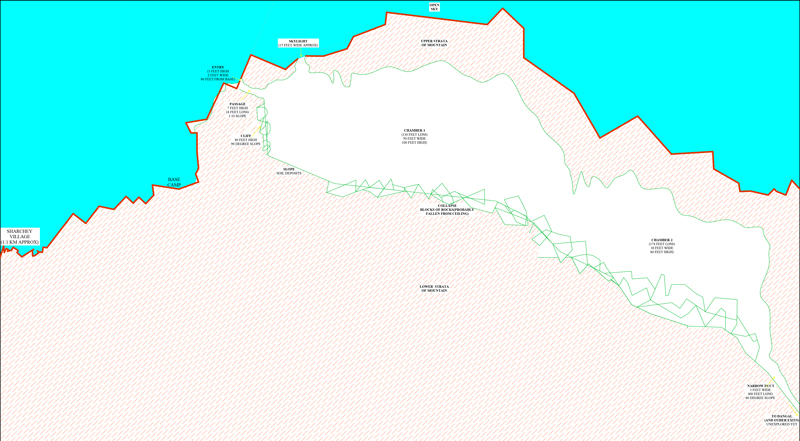

Sectional sketch of rZongi-Kor by Architect Fayaz Ali

Local folklore mentions a cave near the village. Recently, a group of us explored this mysterious cave near Sharchay. This group was led by architect Fayaz Ali who brought the necessary equipment such as heavy torches, rope, measurement tap and gauges etc to measure and explore the cave. In addition, we also had actor Kacho Ahmed Khan who assisted with the exploration, recited verses from the Holy Quran and entertained with his melodious voice. The group included hotelier and entrepreneur Ali Asger, who has considerable experience exploring such caves in India and Nepal, and Zakir Hussain Jaffary, a renowned film-maker and hotelier who documented various facets of the cave. We also had Sadic who is a famous skier and a teacher whose expertise as a mountaineer proved invaluable in this expedition. The group also included local Kargili trekkers, Iftikhar Baravi and Hasnain Rajayee.

The team spent the first night at my home in Sharchay and headed out the next morning after breakfast. It took us to two attempts to find the cave. The cave is known as rZongi-Kor, which is derived from two Dardic words, ‘rZong’, which means chisel and ‘Kor’, which translates as cave. The name suggests that the cave was created and decorated by humans with a hammer and chisel.

The cave is located at the same altitude as the village and is divided into two large chambers. The entrance is through a three-foot high and two-foot wide doorway, which is 80ft from the base camp. There is a 15-foot wide natural façade around the entrance.

The villagers have been following a ritual each time they enter the cave. This ritual has been inherited from our ancestors. When a group enters the cave, one person remains at the entrance reading the Holy Quran. Thus, whenever someone visits the cave, an elder from the village accompanies them to recite passages from the Holy Quran at the entrance. It’s believed that reciting verses from Holy Quran protects the visitors from the dark energies and spirits of the cave.

We honoured this tradition and as we entered the cave, Ali Asgar started reciting Sura Yasin, which is one of the most important parts of the Holy Quran. Once he finished the recitation, we entered the cave. A village elder, Hajji Mohd Reza remained at the entrance to guard it till our safe return. Thereafter, we faithfully followed this procedure each time we entered the cave over the next month that we spent exploring and documenting this cave system

The first chamber of the cave is 50 ft (15.2m) wide,130ft (40m) long and 100 ft (30.5m) high. The second chamber is 174 ft (53m) long, 30 ft (9m) wide and 80 ft (24.4m) high. Beyond the second chamber, there is a duct with a three-foot (0.9m) wide opening and 400 ft (122m) long passage heading downwards at an angle of 60 degrees towards the Indus. The river is below the cave at an altitude of 8,491 ft (2,588m) above msl and meets one of its tributaries in Dangal Batalik, which is about 15 kms from Sharchay.

According to local legends, the cave has multiple exits including one in Gachoo near Chiktan side, which is around 50 kms away. There are folktales in the village that in the past people would use cats to locate various exit points. There is a famous folk-story of two sisters. One sister lived in Sharchay village, while the other lived in Dangal Batalik. The sister in Sharchay village tied a burning torch to the tail of a cat and released it at the main entrance of the cave. A few days later, she heard that the cat had reached her sister after exiting the cave at Dangal Batalik.

We found white marble in the cave, which had been carved into intricate designs including domes and minarets. I am confident that this cave will provide new knowledge of ancient civilisations and the geological history of the Himalayas.

Village elders told us that our ancestors used to store their valuables in the village. In ancient times, robbers from Chilas would occasionally plunder Sharchay village as it was rich in agriculture and horticulture. This forced the villagers to use caves to hide their precious goods. However, one day over 100 robbers from Chilas descended on the village. As they plundered the village, they discovered that the villagers had hidden their precious goods in the cave. They headed to the cave and entered inside to look for the loot. However, none of them were ever seen again. Their fate remains a mystery to this day. One plausible explanation is that they got lost in the maze of ducts and passages inside the cave and died there. People of Sharchay claim that there are human skeletons inside the cave along with metal pieces.

Our exploration of this cave was a fascinating experience. rZongi Khar is said to be the largest cave discovered in Ladakh so far. I penned a poem in the local Dardic (Brok-skat) dialect to celebrate this fascinating fragment of our heritage:

rZongi-Kor Sharchays hove bait.

rZongi-Kor aso bunu taj bait.

rZongi-Kor di azuo hang aaso niwoung.

rZongi-Kor aaso bunu turiwo bait.

(rZongi-Kor cave is the heart of Sharchay,

rZongi-Kor cave is the jewel crown of our vicinity,

There lies our luck over the podiums of the cave,

rZongi-Kor cave is the shining star of our village.

Many aspects of this cave system remain shrouded in mystery. It will require more detailed studies by relevant experts to unearth these secrets. In the meantime, we are creating a documentary film of our exploration, which we hope to release soon.

By Aarif Hussain

Photographs by Zakir Hussain Jaffary

Aarif Hussain (popularly known as Aarif Ladakhi) is a resident of Sharchay village, Kargil. He holds a B. Tech degree in Civil Engineering from Kurukshetra University in Haryana.