My father read the 108 volumes of the Kangyur three times, and the 16 volumes of the ’Bum 35 times. He took up this practice after retiring from his government job. I remember him reading aloud with his steady voice filling our home and also spilling out into the street where it would reach the ears of people passing by. Many would pause and say that simply hearing him brought them a sense of peace. It is said that when holy texts are recited aloud, all forms of life hear them, and peace spreads to every being.

Once, I asked him if he truly understood what he was reading. He smiled and said that he did. That as he read, he could visualise the words, and at times the stories brought the Buddha vividly into his imagination and moved him to tears.

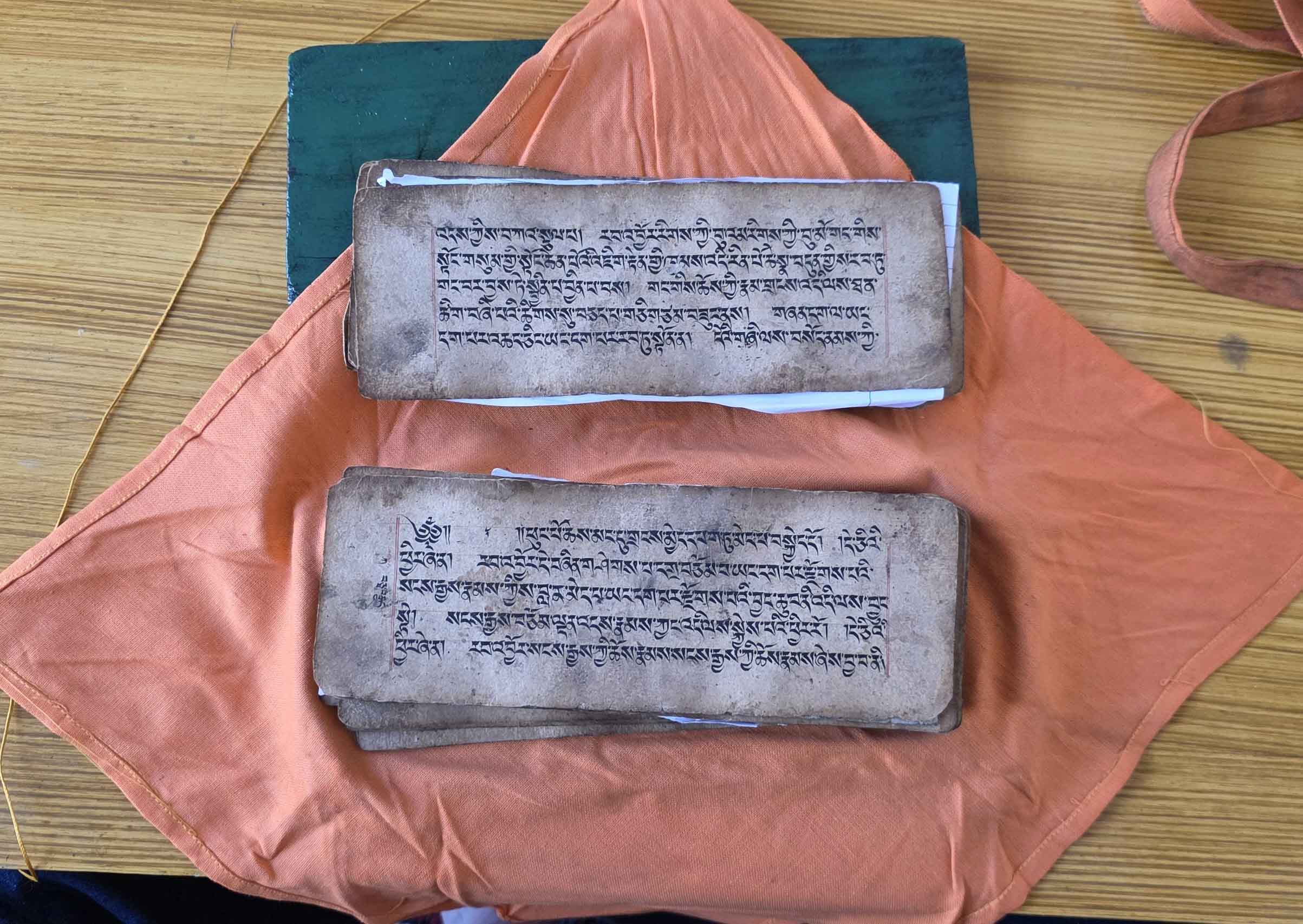

My first encounter with the holy text was with Dorje Chotpa, or the Diamond Sutra. It did not feel accidental. It was as though the book had been quietly waiting for me and was destined, in some way, to be found. In our chapel, a very old handwritten copy on handmade Tibetan paper, rested in silence, as though aware that one day I would turn its pages. I read it once and I did not fully grasp its depth. Later, I returned to the English translation by Red Pine, listened to podcasts that explored its meaning, and continued reading the original script aloud, just as my father once had. What unfolded was a gentle dialogue between the Buddha and his disciple, Rabjor. It felt alive rather than distant. The words themselves seemed to carry a subtle energy quietly imparting the wisdom I was ready to receive and needed: That all things including various phenomena, states, and conditions, arise and pass, never lasting and never fixed.

It is said that to hear or read the Diamond Sutra is itself the result of great merit that one must have earned the fortune to encounter it. Tradition also holds that the very place where the text is kept becomes blessed by its presence.

Through my research, I discovered something remarkable. The honour of being the world’s first printed book in recorded history belongs to none other than the Buddha’s Diamond Sutra or Dorje Chotpa. In fact, it is the oldest known complete printed book with a definitive date.

In the Diamond Sutra, one frequently comes across the phrase, “Thus have I heard,” which suggests that the text was not a later invention, but rather a record of an actual event. The words, “Thus have I heard” are understood as the direct notation of an eyewitness account, i.e. notes taken and preserved, which became the Dorje Chotpa.

The event itself is introduced as: “Thus have I heard. Once upon a time, in the Jetavana Monastery at Shravasti…”—a place that still exists today. The Dorje Chotpa narrates a true historical moment of a sermon delivered by the Buddha to 1,250 disciples with Rabjor, the eldest and wisest among them, asking the questions.

For me, Dorje Chotpa describes a deeply conducive learning environment. The very first chapter sets the scene in a manner that I would regard as the ideal classroom. It presents the Buddha as the ideal teacher: Humble, prepared, and impartial. Before delivering his sermon, he walks from house to house, accepting whatever food and alms are offered, treating everyone equally, showing no preference, no pride, and no favouritism among his disciples. The dialogue unfolds with Rabjor posing thoughtful queries, and the Buddha, pleased with each, often exclaims, “Excellent!” encouraging him to ask more. As I continued to read, I noticed how each response was layered, full of examples, open to many different ways of being understood. I was particularly struck that the one asking all the questions is described as the eldest and wisest. Somehow, that makes me pause. It reminds me that wisdom does not bring an end to inquiry even for the Buddha’s eldest disciple, Rabjor. Learning never really ends and there is no final state of mastery. The text also emphasises that knowledge should not be hoarded; it must be shared. Knowledge itself is not static. It keeps on evolving as it propagates. In the same way, it teaches the practice of generosity—giving freely, without any thought of return. Such an act, the Buddha explains, carries immeasurable merit. To Rabjor, he points out that while offering material wealth is indeed noble, there is a merit far greater—vast as the countless grains of sand on the bed of river Ganges, boundless as the infinite directions of east and west—in the sharing of knowledge and wisdom.

The book also teaches us not to take pride in power, status, health, position, or fame and that all of these are transient. Life is followed by death, health by disease, and even the universe itself is impermanent. One message in particular stands out to me as deeply important: The text teaches us not to become obsessed with even our own religion but practice its principles. The Buddha advises Rabjor to regard his teachings as a boat to cross a river, which should be used to reach the other shore and then left behind.

The earliest printed copies of the Dorje Chotpa still exist in the British Museum in London. At the end of the text, there is an inscription stating that it was printed by a son in memory of his late parents for their salvation. Remarkably, it is the belief that merit can be earned by spreading the wisdom of the text has helped it endure through history and ensured that it has been preserved as the world’s first recorded printed book.

In short, the Diamond Sutra teaches us about impermanence. At one point, a disciple asks the Buddha the name of the sutra he was teaching. He replied, “Dorje Chotpa, the Book of Highest Wisdom.” He advised them to memorise the name but told them not to cling to it as a great book. He said, “Read it, awaken your mind, and achieve realisation. Don’t get attached or worship it as a great book but practice the sutra and propagate its teachings, even if it is just four lines.” Then he concluded by saying, “What is in a name?” thus emphasising the fundamental truth of impermanence. For these reasons, Dorje Chotpa is regarded as the book of highest wisdom. It has been printed and propagated, often in loving memory of someone dear. This is a book to be read, understood, and embraced with faith. Its wisdom is said to endure until the end of the world. This is true not only for the Diamond Sutra but for all great texts: One should not cling to them, but read, understand, and practice their teachings.

By Dr Spalchen Gonbo

Dr Spalchen Gonbo is a Paediatrician based in Ladakh.