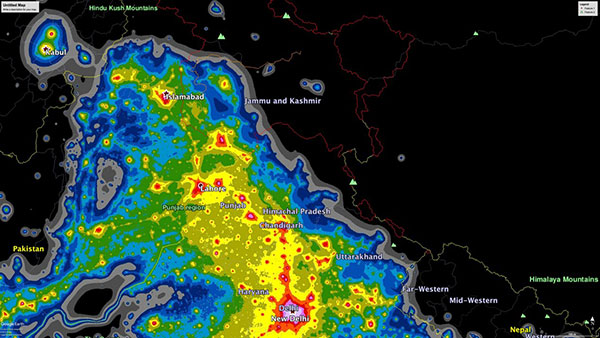

The Trans Himalayan region of Ladakh is located at the junction of collision between the Indian and Eurasian tectonic plates. The formation of the Himalayas started with the closure of the Tethys ocean around 65 million years ago. The region has a mesmerising landscape with a diversity of geomorphic and geological features. It has a rich and fascinating heritage owing to its unique geographical location. The area comprises wide glacial valleys, majestic mountains, saline and freshwater lakes, sand dunes, and lunar-like surface features. The region’s extraordinary geology has attracted many geoscientists, environmentalists, researchers, and nature lovers from around the world.

Ladakh is a natural laboratory that holds evidence of Himalayan mountain-building process. It has rocks formed at high temperatures and high pressure deep inside the earth that are known as eclogites, which can be observed near Sumdo in Changthang, eastern Ladakh. One can also observe rocks like pyroxenite, serpentinite, harzburgite, lherzolite, dunite, and gabbro, which have crystallised at high temperatures along the Indus and Shayok valleys. As a result of the closure of Tethys ocean, underwater rocks such as ophiolites can be observed in different parts of Ladakh including Nidar and Zildat areas in the east, Shargole in the west, and Spontang, Zangskar in the south. The presence of such rocks provides a unique and rare opportunity to study ocean floor processes. In addition to ophiolites, the erstwhile ocean floor includes fossil-rich limestone, which gives us an opportunity to understand past marine life. This includes fossils of marine life as well as freshwater fossils of plants and animals dating back millions of years.

The Indus river valley is tectonically unstable due to the continued mountain-building process. This has resulted in variations in topography, height of landscape, and sedimentation causing mass movements, and shifting of sediments to valley floors. Owing to these tectonic disturbances, lakes have been known to form due to damming of the Indus for different time spans at various locations in the geological past. In time, sediments would accumulate over the lake floor and once the lake would drain due to outburst floods caused by tectonic activity, the sediments would get redistributed.

These lake deposits are one of the most informative, best-documented, and well-preserved sedimentary archives along the Indus river, which is significant geological evidence of the palaeo-lacustrine environment and a research asset for palaeo-climatic studies in Ladakh. The sequence of lake sediments offers us an opportunity to infer past climatic changes, understand complex geomorphic processes forming a variety of intertwined landforms, and vertical variations in minerals, and to decipher changes in the source of sediments. It also preserves the imprint of past climate and tectonic events that can be used to interpret the climate-tectonic inter-relationship in this geologically active region where glacial and fluvial processes have played an important role in landscape evolution by depositing, blocking, and diverting drainage courses. Such palaeo-lake sites including Spituk (Pethub), Guphuks, Zingchen, Khaltsi, Lamayuru, Achinathang, Hanuthang, Byama, and Akchamal along Indus Valley and Khalsar along Shayok and Tangtse river valleys have immense scientific and educational value.

Granitic bodies extend from the Astor-Deosai-Skardu region to the Lhasa region in Tibet and are evident throughout the Trans Himalayas along a west-to-east axis. These granites are exposed in Ladakh and in geology they are known as Ladakh Granitoid Complex/Ladakh batholith, which consists of a variety of granitic rocks including tonalite, granodiorite, diorite, porphyritic granite, etc—each of which exhibit different textures. These granitic rocks are mineralised with quartz, feldspar, mica, hornblende, tourmaline, etc. The compositional studies of these granites could provide clues to their genetic environment.

Ladakh region is endowed with rich mineral wealth of economic importance. Some of the important minerals that occur in Ladakh are aquamarine beryl crystals in granitic rocks exposed between Hemya and Gaik areas, chromite mineralised in rock bodies of Kyun Tso-Shurok-Sumdo areas in eastern Ladakh and on the way to Marpo-la from Drass in Kargil. Malachite and azurite (copper ores) are present as stains near Basgo in Leh and the confluence of Suru river and Pinjung Nala in Kargil. Gypsum is present in the form of beds and lenses at Phitsi Nala in Zangskar valley, Kargil district, and Puga valley, Leh district. A considerable quantity of magnesite and marble has also been reported from Ladakh. The Himalayan granites possess a high concentration of uranium, thorium, and potassium, which are responsible for the generation of geothermal energy that is evident in the number of hot springs in Ladakh including Panamic, Puga, and Chumathang along with deposits of sulphur, borax, and fluorite mineralisation respectively.

Ladakh is a treasure trove that attracts visitors from around the world to experience and study the remarkable landscapes and landforms that are found in the region. Given its exceptional geology, riches of natural resources, and fragile environment, Ladakh is regarded as an important geo-heritage region that needs urgent attention to prevent possible destruction. These areas are important for school and college-level educational activities as well as scientific studies related to natural hazards, groundwater, environmental changes, geological history, etc. In this context, local communities and the government need to work together to conserve these geological treasures. This will require public awareness, legislation, documentation, and research to systematically preserve these sites while still enabling developmental changes.

Text by Dr. Stanzin Namga and Dr. Meenakshi

Photographs by Stanzin Oldan

Dr. Stanzin Namga is a faculty member at the Department of Geology, University of Ladakh

Dr. Meenakshi is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Department of Geology, University of Ladakh

Stanzin Oldan is a student at Jamyang School, Leh.