Noor Jahan and Wajeeda Tabassum graduated in commerce and their families wanted them to pursue a career in the corporate sector. Noor Jahan explained, “I was not happy with what I was studying at college and was not really interested. My family wanted me to study commerce, take a job in a bank or pursue an MBA degree. I felt like I was wasting time.”

Noor Jahan returned to Leh after completing her graduation. While walking through Leh’s old town neighbourhood she noticed some people working on the conservation of Chamba Lakhang. She was intrigued and approached them for a short chat. After returning to Delhi, she started reading about architectural conservation and learnt about the possibility of pursuing a post graduate degree in this field. At the time, Wajeeda was completing her Master’s in Sociology in Delhi. Noor Jahan told her about what she had learnt about conservation, which got Wajeeda interested too. “During our research on conservation we learnt that there is a lot of scope in this field,” added Noor Jahan.

They found relevant courses at two institutes: National Museum Institute and Delhi Institute of Heritage Research and Management (DIHRM). The National Museum Institute course required graduation in history, design, and an art-related background. The DIHRM course was open to people with different backgrounds. Soon, Noor Jahan and Wajeeda enrolled for a Master’s in Conservation at DIHRM after clearing their entrance examination.

After attending the theory class for the first year, they had to do an internship. Generally, students from DIHRM intern in Delhi where the institute collaborates with the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH). However, Noor and Wajeeda opted to do their internship in Ladakh with Himalayan Cultural Heritage Foundation (HCHF). “We got in touch with Dr Sonam Wangchok, the Founder Secretary of HCHF and he was very supportive. We got an opportunity to work on three projects for our internship. Dr Wangchok suggested we intern with the restoration work of the Chorten in Shey, which was underway at the time,” said Noor Jahan.

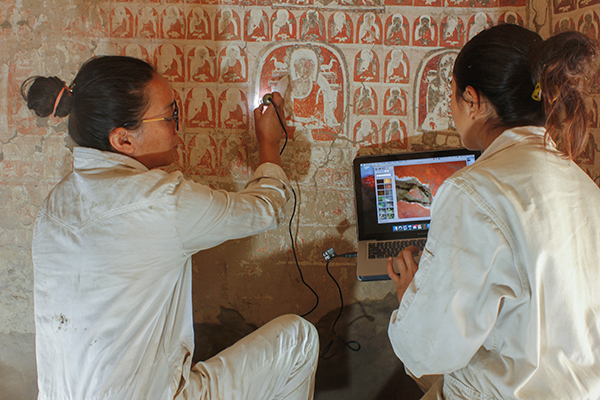

While working on the restoration of the Chorten, they met people from different walks of life, which expanded their understanding of the field. As part of the internship, they also helped document rock sculptures in and around Leh. In addition, they also worked on wall painting conservation in Nubra with a team from the Czech Republic. “We were very happy as we got to work on what we had studied in class. It was a very good experience and we learnt many basic aspects of wall painting conservation. The internship with HCHF gave us a lot of experience. We also became aware of the vast scope of art conservation in Ladakh,” explained Noor Jahan.

After completing their masters, they got in touch with wall painting conservator and a member of the firm, Art Conservation Solution (ACS), Sree Kumar who has been working in Ladakh on wall painting conservation. That year, ASC had a project in Igoo and Sumda Chun, which Noor and Wajeeda were able to join. This was their first wall painting conservation project. “We were so excited with the work and learnt more about wall painting conservation. We had intended to volunteer but they ended up paying us,” said Noor Jahan. Later that summer, the second phase of the work in Nubra by the team from Czech Republic also started. “We joined them once again but after working with ACS we saw many differences in how they work and this raised many questions. The team from the Czech Republic engaged in extensive retouching. So, if a painting is lost, they would recreate it,” recalled Noor Jahan.

In September that year, a firm called Heritage Preservation Attire from Chandigarh called them to work on a conservation project at the Golden Temple in Amritsar. This was their first experience in working with a lime base painting, which helped broaden their expertise. “These experiences have broadened our knowledge and skills in conservation,” explained Wajeeda. By this time, they had enrolled for a PhD as they had become interested in exploring different aspects including materials, techniques, colours etc of wall painting and artefacts. “During project work we do not get time to study details of the wall paintings. It is very important to understand the work before starting the restoration process. Otherwise, you may end up adding new things to an old painting,” said Noor Jahan.

They continued working on various such projects. They had also started discussing the idea of establishing an independent entity to work with heritage conservation. “In 2017, we were discussing the possibility of starting Shesrig Ladakh. One day, I was sitting in a café in Leh bazaar and the Masjid Sharif had just been dismantled for restoration. I saw this house (Choskor house) and thought it would be ideal for our work. That evening, I called Wajeeda and told her about this house. Early the next morning, we explored this old house and imagined that it could be developed as a working studio for conservation of artefacts,” explained Noor Jahan. They got in touch with owner of the house and started restoring it using their scholarship money. Later, Achi Association helped restore the interiors of the house. The Shesrig Ladakh conservation studio will open in May 2022 in the 200-year-old Choskhor house in Leh.

The main objective of establishing Shesrig Ladakhis to make art conservation more sustainable in Ladakh and contribute to Ladakhi society. “We could easily have taken a job outside or even in Ladakh, but after we chose this field we decided to work in and for Ladakh. This work has kept us connected with Ladakh and helps us contribute to the conservation of its rich heritage. We are part of the local community and must contribute back to society. I can’t even think of working outside Ladakh. Another aim is to make this field sustainable because many conservationists work in Ladakh on a project basis and it is seasonal. We want to make this field active throughout the year as a lot of conservation work needs to be done in Ladakh,” added Noor.

Shesrig Ladakh is also making an effort to engage local youth in conservation to help them understand the field. “There are many skilled youngsters, especially girls, and we are trying to give them exposure. Studying about conservation is important. Even if someone has not studied conservation but has the necessary skills and interest in conservation, we have a responsibility to provide them with training and exposure. If I can educate someone about heritage then that person can educate others and help expand the chain of learning about heritage. As of now we are at the initial stage and it will take time for this idea to grow. There will be struggles along the way,” expressed Noor.

She explained that establishing the studio is important. “We have to work on the site for wall paintings but there are many artefacts that can be brought to one place for restoration. Many people can also be engaged in this work. Right now, two girls are freelancing with us. We cannot give them a full-time job yet. When the studio is functional, we could give them full time work and engage others,” said Noor.

They have also faced many challenges. One of the main challenges at sites is accessibility. Wajeeda explained, “Working in Ladakh is one of the best experiences I have ever had but it comes with many challenges. The remoteness of various sites and the lack of expertise in the field are big challenges.” Many old monasteries and structures are located in isolated sites and it is difficult to carry material and equipment to them. Conservation materials and supplies are often very heavy. “In 2020, we worked on the conservation of Chomo Phu, a 13th Century temple in Disket, Nubra. It is a single room gonpa. There was no place for accommodation so we stayed in tents and had to improvise basic facilities. This is common for many sites. People are very supportive wherever we work. Ladakhis know the importance of conservation of old paintings and many people come forward to help,” added Noor.

Another challenge they face is the lack of systematic funding from the government. “There are funds for structural conservation but not for paintings within the structure or for the conservation of artefacts. It seems that the government is not able to support this work as most of our paintings and artefacts are religious in nature. We need to develop a sustainable model to support conservation work,” Noor said. She added that many times contractors carry our structural conservation work. “What would a general contractor know about conservation? They lack expertise and there is a danger of damaging these ancient structures and their heritage value. It is better not to do anything at all instead of destroying it,” worried Noor.

Wajeeda agreed and said, “Sometimes priceless heritage gets damaged even by professional conservators who may lack understanding of the condition and challenges in Ladakh, limited knowledge of techniques and materials or be aware of the long-term impacts of using incompatible material. This can cause irreparable and irreversible damage.”

Finally, they spoke of the need to have a heritage committee and the adoption of a heritage policy. “In Ladakh, this is regarded as a noble profession but everyone’s intentions are not clear. Sometimes people with good intentions can also cause harm. Similarly, when someone from outside Ladakh works on conservation, he or she may not know about many aspects of the painting unless he or she has studied them intensively. For example, in Karsha Gonpa, when experts were called for the conservation of wall paintings, they started to work but they were not able to bear the cold and took the wall painting to Lucknow. Many such things could happen unless we have someone regulating and overseeing conservation of our heritage. Similarly, we have also seen cases of artefact theft in the name of conservation. This is a big issue,” Noor stated. She added that a heritage policy guideline is required with a heritage committee to oversee conservation work. The heritage committee must verify the work of the conservationist. In addition, we need to have a dedicated person at the Hill Councils to look at matters related to heritage.

Wajeeda added, “We have seen a definitive increase in awareness of our cultural heritage but we have a long way to go. We should incorporate cultural heritage awareness in schools. In addition, museums in Ladakh should serve as educational institutions rather than tourist attractions. Museums can play a very important role in spreading awareness of our cultural and material heritage.”

By Kunzes Dolma

Kunzes Dolma is part of the editorial team at Stawa.